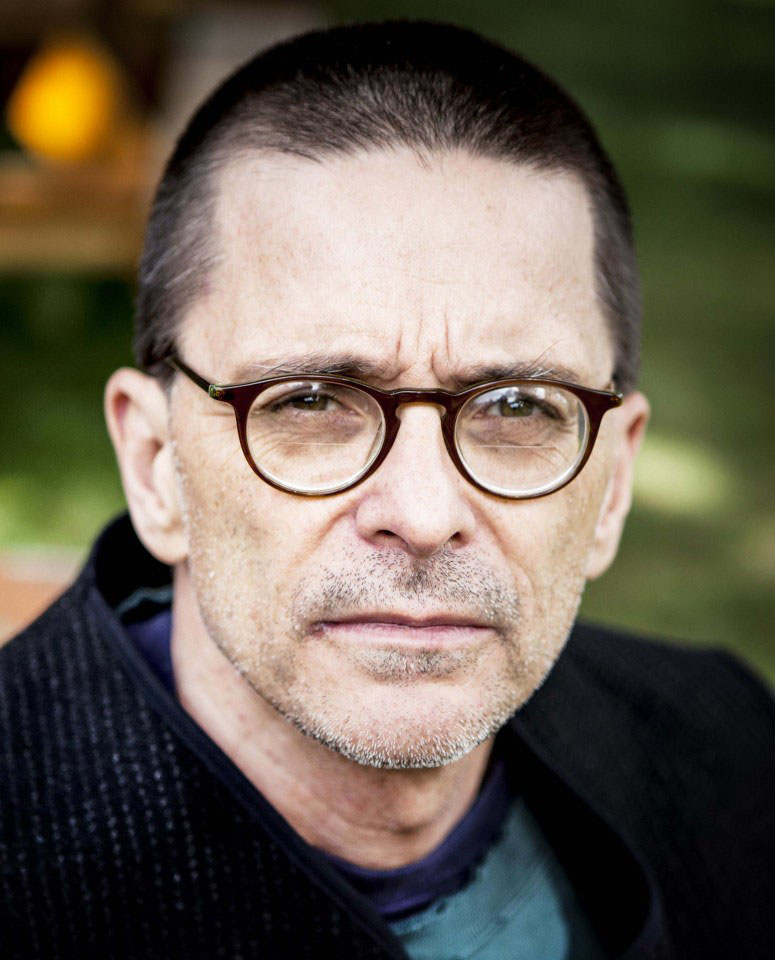

Dr. Robert Jensen is a Professor at the University of Texas at Austin. He specializes in media, law, and politics. Here we talk about his background and views, especially around patriarchy, pornography, and radical feminism.

Scott Douglas Jacobsen: What was family background regarding geography, culture, language, and religion or lack thereof?

Robert Jensen: I grew up in North Dakota, born in a small town in North Dakota, spent most of my childhood in Fargo, North Dakota, which is the big city. All of 60,000 people when I was a kid. Both parents are white. I attended and was confirmed in a middle of the road Presbyterian church.

Although, religion was not a big part of my household. It was more of a social obligation than a theological enterprise. As soon as my parents stopped compelling me to go to church, I pretty much stopped going.

Jacobsen: Without being compelled to go to church, within that community, 60,000 people, was that a common reason for going, the parental push to attend whatever particular service was being held at the time? Is that a common experience?

Jensen: I think it was common in the church I attended. I am sure it was not necessarily the norm everywhere. Fargo was a fairly small city in the West. We are talking about the early ‘60s and 1970s. There were more Evangelical churches.

There were traditional Roman Catholic churches. It was much a Christian enterprise. It was a small Jewish community, at least one, maybe two synagogues. I do not remember. But in the world I grew up in, there was little religious fervor.

On the part of young people that were part of my social set, there were other social sets. There is an Evangelical tradition in high school/college age kids, Campus Crusade for Christ things.

I am sure they existed, but they weren’t part of my direct, immediate circle.

Jacobsen: Once you left the church community and entered undergraduate training, what became the main interest in things like ethics and politics and law?

Jensen: I graduated from college in 1981. I spent my 20s working in mainstream newspaper journalism. So, I was a working journalist and the way mainstream journalism in the US works is you do not have much time or space to develop a political philosophy.

You’re chasing the story of the day. You’re engaged in coverage of social issues, politics, economics, all the time. But at least for me, and I think it is not an unusual experience for younger journalists, there is no overall political philosophy that you tend to think about.

In that sense, you accept the existing range of political ideologies that are in the mainstream, which is basically, hard, right-wing reactionary conservatism to a mushy liberalism, in the mainstream in the US.

In other words, the politics defined by the two major parties. I did not start thinking about these things in a deeper way until I went back to graduate school when I was 30-years-old. I was exposed to different ways of thinking, including more radical critiques of mainstream society.

Through feminism critiques of white supremacy, critiques of capitalism, critiques of US imperialism, and a deep ecological critique, I started developing all of that, those ideas, halfway through my life at the age of 30. I am about to turn 60.

The last 30 years, I have been engaged in that. None of that ever came up when I was growing up. None of it came up in some sense in undergraduate education. I do not think that the existing school system in the United States challenges people to think deeply about these things.

Jacobsen: You published a book in 2017 entitled The End of Patriarchy: Radical Feminism for Men. What best defines radical feminism? What makes the emphasis on men in that particular text important as a note in the canon, so to speak, of feminist literature?

Jensen: So 30 years ago, my first entry into political activism and philosophy, ethics, law, and political philosophy was through feminism, specifically the feminist critique of the pornography industry. That is a set of ideas often associated with what we call radical feminism in the US.

Now, any term like radical is going to be understood differently by different people. When I use the term, I am going back to what is typically called second wave feminism in the United States. The movement that grew up in the 1960s and ‘70s, coming out of the general ferment.

Of the 1960s, radical feminism looked at the foundational structure of patriarchy in contemporary societies, institutionalized male dominance rooted in men’s attempts to control or claim ownership over women’s bodies.

Which means primarily reproductive power and sexuality, radical feminism shares some ideas with other brands of feminism, but it tends to focus a lot on the way that men control women through reproductive means as well as through sexual exploitation.

So, the radical feminist perspective is most often known for its critique of what I call the sexual exploitation industries—pornography, prostitution, stripping. The way men routinely buy and sell women’s bodies for sexual pleasure in a patriarchal society.

So, radical feminism is a way of thinking about oppressive and rigid gender norms in a society rooted in patriarchy and men’s attempts to control and claim ownership over women. It tends to highlight in the contemporary era the way that plays out in the sexual exploitation industries.

Beyond that, for me, radical feminism is also a way of thinking about power more generally. What radical feminism did for me 30 years ago was pointing out, that we live in a deeply hierarchical society where there is the assumption of domination and subordination.

That is, the assumption that the world is going to be structured on some group of people being dominant and some other group being subordinate is routinely accepted. What radical feminism did for me is to help me focus on the profound immorality of hierarchies, hierarchies in human societies.

So for me, radical feminism is a way of looking at the world. It is a way of looking at gender in patriarchy and it is a way of looking at specifically contemporary practices of pornography and prostitution and providing a critique of why those patriarchal practices are inconsistent with a stable, decent, and human community.

Jacobsen: The majority of users, if I am not mistaken, of pornography are men, by a vast margin.

Jensen: Correct.

Jacobsen: What are the typical appeals, in terms of types of pornography for men? How does it differentiate from the super minority of women who use pornography?

Jensen: So first of all, pornography requires a definition from the perspective of the radical feminist critique I work from. Pornography is not an attempt to represent in language or in visual media: sexuality.

It is a particular presentation of sexuality within that domination-subordination dynamic of patriarchy. We look specifically at the contemporary pornography industry, which is the product of the last half-century.

There have been pornographic material before that, but the incredible explosion of the amount of graphic, sexually explicit material in contemporary culture is a post-World War II phenomenon.

The radical feminist critique focuses on that contemporary reality. As you pointed out, the vast majority of consumers are male and therefore the industry tailors its products for men. Specifically, for men in patriarchy, where there are other hierarchies in existence, it does it to generate profit.

As a result, the images tend to reflect the male sexual imagination in patriarchy, which is a fusion of sexuality with power, so the images are routinely of men in dominant positions over women, images of men obtaining sexual pleasure through the subordination of women.

Women routinely embracing their own subordination. Now, that’s a broad statement about a pattern. There are literally, of course, millions of pornographic images in the world, so there will be considerable variation.

But the radical feminist critique tries to look at patterns and observes that at the core of contemporary pornography is eroticizing or sexualizing that domination-subordination dynamic. The fundamental dynamic is male over female.

But pornography also sexualizes other forms of inequality. For instance, pornography is the most, without a doubt, overtly racist media genre in the world today. In pornography, you see crude, grotesque racial stereotypes employed.

It is another way of sexualizing hierarchy and inequality. Now, as I said, that’s an observation about general patterns. But there is variation. There are also women who use pornography. Some women use pornography that’s produced essentially for that male clientele.

There are smaller genres of pornography in which the producers claim to be trying to create women-centered porn. There is a lot of variation. The focus of our critique and the movement is on the overwhelming majority of those images.

Constructed for men and reflecting a male sexual imagination as its constructed in patriarchy. Now, it is important to point out. We are not arguing that is the way all men think or the only way men can think. We are talking about a way male sexuality is constructed in patriarchal societies.

The movement implicitly is arguing for a different conception of gender, sex, and power.

Jacobsen: What are some responses that those on the other side, or with one of the other countervailing positions, what are some of the responses they might present? How would you respond to those critiques?

Because I am not as familiar with the literature as much as you are.

Jensen: There are defenses and celebrations of pornography, of course. Some come from mostly liberal perspectives. But some even come from other wings of the feminist movement. I think they sort out into two or three main kinds of responses these days.

One is that there are people including feminists who will say, “The radical critique of pornography is accurate. It is consistently a form of sexualizing domination. But there can be no collective response to it out of a fear of sexual repression.”

So, that would be a traditional liberal response. That we must preserve individual choice at all cost and while much pornography is sexist, racist, and rooted in hierarchies. We have to live with it.

Another perspective would celebrate pornography as a place for sexual liberation. I do not know how to define that position because I find it quite odd that you can take a genre of pornography that is so overtly, relentlessly misogynistic and racist.

Imagine, that it is a place for positive, progressive sexual liberation, but people do make that argument. I think that’s rooted in another basic liberal perspective, which is that you cannot make judgments about sexuality.

I think it is a misguided perspective. A more recent phenomenon is a perspective that says, “Okay, a lot of the porn industry produces material that is politically and morally objectionable. That is, it undermines any hope of women’s freedom in the world.”

“But we want to keep open space for what is sometimes called Feminist Pornography. The idea that if women were put in charge, they would create different kinds of images.” In fact, as I said, there is a lot of variation in the production of pornography.

The segment of the market that one could meaningfully call feminist or progressive is tiny. The vast majority of images reflect the patriarchal nature of contemporary culture. People do try to defend or even celebrate pornography.

I have been paying attention to this issue for 30 years and I have read a whole lot of defenses of pornography, and I must say, I have never found one that’s terribly compelling. I think that reasonable people can disagree about policy perspectives.

That is, what should the law say about pornography? I think that’s a difficult question. I do not think there is any easy answer to it, and people certainly, depending on their political philosophies can disagree.

But the basic analysis of the porn industry and the patriarchal nature of it seems to me not only to continue to support the feminist radical perspective, but even more so. One of the interesting things about radical feminism is that the critique it offered in the 1970s of pornography.

Of that era, you’re not old enough to remember this.

Jacobsen: Ha, that’s true.

Jensen: But the pornography of that era was by contemporary standards quite tame. But the radical feminist critique, which saw that the domination-subordination dynamic at the heart of pornography of that era has only been proved correct by time.

Where the expansion of the porn industry and the incredible demand for it in the culture has meant that the trajectory of the industry has been, as you would, predicted from the radical feminist critique, a deepening of that domination-subordination dynamic.

An expansion not only in the amount of it, but in the intensity of the misogyny and racism of it. So, the irony is that the radical feminist critique, I think, over roughly 40 years has been developing.

It has been proved correct. Yet, the radical feminist perspective is in some sense more marginalized than ever. But I still after 30 years see no reason to abandon the radical feminist critique.

The opposite, it seems more compelling than ever.

Jacobsen: Every moment and discipline have their bright lights and their seminal works, whether papers, essays, or books. What individuals made bigger impacts than others in the 30 years you’ve been in the field?

What essays, articles, or texts have made a similar impact as those individuals?

Jensen: So, every idea in politics comes from a collective effort in some sense. But the person who is most clearly identified with the feminist critique of pornography is Andrea Dworkin.

Andrea wrote a crucial book that came out in 1979 called Pornography: Men Possessing Women. Which laid out the feminist analysis, that I have been summarizing and from which I continue to work.

She wrote another book, a collection of essays and speeches that were published in 1985, might’ve been ’84, but I am sure it is ’85: called Letters from a War Zone. That I consider in some sense her best work.

But those two books did a lot to define the radical feminist critique of pornography. The other person most associated with this, a feminist legal scholar named Catherine McKinnon, who’s also known for her early work on sexual harassment law.

Catherine McKinnon and Andrea Dworkin came together in 1983 to propose a new approach to the law around pornography, arguing that the traditional obscenity law that’s part of criminal law should be replaced by a civil rights framework.

There was a lot of political activity around that in the 1980s. So, that what’s generally called the feminist civil rights perspective on pornography is associated with those two women, Andrea Dworkin and Catherine McKinnon.

Dworkin died, gosh, more than a decade ago now. Catherine McKinnon is still living and still working. After that, I think the person in the book most important was written by a friend of mine, named Gail Dines.

That book is called Porn Land. The subtitle is something close to how pornography hijacked our sexuality, or how the pornography industry—I am not in my office so I do not have the book in front of me. That was published in 2010.

And Gail is undoubtedly the leading feminist critic of pornography today. She is British born, but lives in the United States. Porn Land was an important book that not only updated some of the trends in pornography production and content, but also looked at the shifting nature of the pornography industry.

Gail, I think, is the leading expert on that, on the pornography industry and its methods of production and distribution, which, of course, change considerably on the internet. So, I think those three women are the key thinkers in the United States around this critique.

Jacobsen: Since radical feminism discipline is also a movement, what would you evaluate as a positive trend in the next 5 years? What would you evaluate as a negative trend in the next 5 years for the movement?

Jensen: Let’s start with the positive.

So, as I said, there are other feminist perspectives on pornography and those other perspectives, which I’ll call generally liberal and post-modern, traditional liberal feminism, and this more recent development of a postmodern feminism in the last 20 years or so.

If you go into academic feminism into the typical women’s studies department, you will find that liberal and postmodern feminists dominate and radical feminism is either absent or largely on the margins.

I think the positive is that the trajectory of the pornography industry producing ever more graphic, sexually explicit material that’s increasingly cruel and degrading to women, increasingly overtly racist.

This concerns ordinary people. Young people often are concerned about growing up in a world where this is the standard sexual imagery. Parents are worried about how to educate kids about healthy sexuality when they are exposed to this material from preteen years onward.

The easy access to a computer too. So, even though the radical feminist critique I articulated is out of fashion in certain academic’s spaces, when ordinary people hear that critique, they find it compelling because it answers questions they are asking in their own lives.

So, I have seen an increase in the last 5 to 10 years of interest in the radical feminist critique. I think precisely because it is such a compelling analysis. That’s the positive. Those people are increasingly frightened by the direction the pornography industry has gone.

They are looking for answers. The negative is that we live still in an intensely patriarchal society in which feminism has made progress, for instance, reforming rape laws since the 1960s. But the #MeToo movement of the last 6 to 9 months has pointed out how ubiquitous male sexual violence is, whether it is sexual harassment or sexual violence itself.

So, we still face this overwhelmingly patriarchal society that turns out to be overwhelmingly resilient. While women’s experiences of sexual intrusion are being talked about more and we are more concerned about it as a society, at least one would hope we are, the pornography industry goes forward unchecked.

I think that the #MeToo movement both creates space to point out connections between the way we imagine ourselves and represent ourselves in media and the way people are socialized to think about themselves.

So, it seems to me that the current climate reminds us of how brutal a patriarchal society is, but one can hope this opens up space for news of talking about it.

Jacobsen: Thank you for the opportunity and your time, Professor Jensen.

Jensen: No, my pleasure.

Scott Douglas Jacobsen founded In-Sight Publishing and In-Sight: Independent Interview-Based Journal.