When religious accessories come up for debate, one of the inevitable arguments made for banning them is that they’re “symbols of oppression”. It’s such a common justification that I felt it worth pulling out and tackling separately.

You’ve heard this argument. You’ve probably made this argument. It’s very popular. It’s not always made specifically to justify religious accessories bans. But it very often is. , in Québec, as debate rages about banning religious accessories, the current Minister for the Status of Women, Isabelle Charest, made a public statement calling hijabs a symbol of oppression. She even went so far as to say that the hijab is is not something that women should be wearing

.

I am not going to discuss the question generally; I am not going to debate whether religions are generally oppressive. I’m just going to focus on the claim specifically as a justification for a religious accessories ban. If you really want to debate whether religions are oppressive generally, leave it for another day.

This one’s going to go long, not because it’s a complicated idea, but because there is so much whataboutery connected to it. I’m not even going to cover it all, but I am going to cover the most popular stuff.

Let’s start by picking apart exactly what’s being said when someone tries to justify banning religious accessories because they’re “symbols of oppression”.

What does it mean?

So what exactly is someone saying when they call religious accessories “symbols of oppression”? Well, there are two different answers:

-

They might mean that religions in general are oppressive. What exactly that means (existing religions are oppressive? the very idea of religion is oppressive?) is beyond the scope of the discussion here. The point is that religions are oppressive, and thus all symbols of religion are symbols of oppression.

-

They might mean that specific symbols are symbols of oppression. So, for example, a crucifix on a necklace is not a symbol of oppression, but a niqab or burqa is. What makes a specific symbol oppressive is that:

- it is (sometimes/often) forced on the wearer (and sometimes/often by significant coercive authority and not just cultural standards or expectations)

- it is applied unequally, usually only to those with less cultural/social/political/legal power

- it is unnecessarily restrictive or cumbersome; or

- it dehumanizes the wearer somehow.

In either case, the argument is that since the symbols represent oppression, it is inappropriate for them to be worn while working a government job. The comparison is often made to the Nazi swastika – because of course it is – or the KKK hood and robes. Obviously we wouldn’t tolerate someone showing up to work wearing a Nazi swastika or KKK hood, the argument goes, so why do we tolerate symbols of oppression just because they’re religious?

Well, let’s get into it.

Fact versus opinion

How good do you think you are at determining which statements are facts, and which are opinions?

I’m not trying to be rude in asking that. It’s a serious problem. Arguably it’s one of the most serious problems of our time, perhaps second only to climate change (and the climate change problem is exacerbated by it!) This is why all the “fake news” and media manipulation we’re dealing with is actually working.

This is not about “true” or “false”. Whether a statement is factual or an opinion has nothing to do with whether it is true or false. Factual statements can be either true or false. Opinion statements are neither true nor false, and never can be.

- “Science has found no connection between vaccines and autism.”

This is a factual statement. And it is true. It is objectively true, because if anyone disagrees, we can point to object measurements and observations that verify it.

- “The Earth is flat.”

This is a factual statement. However, it is false. It is objectively false, because if you want to believe it is true, you need to go out of your way to ignore all the observations and measurements that verify it.

- “Atheism is immoral.”

This is an opinion statement. I disagree with it, and most people I consider decent human beings do as well. However, there are no objective measurements or observations one can make that would prove it either true or false. Even if you could somehow objectively show that all atheists are decent, moral people – which is also impossible – that would only prove that atheists can be moral… which could happen even if atheism itself is immoral. (Atheists of all people should realize that it’s quite common to believe in immoral doctrines, but still be decent people.)

- “Country music is a crime against humanity.”

This is an opinion statement. I agree with it. There is no way to prove it empirically. But it’s totally true™.

, Pew tested over 5,000 Americans. They found that only 26% could correctly label 5-out-of-5 factual statements, and only 35% could correctly label 5 opinion statements.

Do you believe you’re not only above average, but that you’re in the top quartile? Sure that confidence isn’t just Dunning–Kruger in action? Try the test yourself, and see how you do.

So, is the following statement a factual statement, or an opinion statement?: “The burqa is a symbol of oppression.”

The answer is: It is an opinion statement.

And because it is an opinion statement, that means it can neither be true nor false.

So it is not “true” that religious accessories are symbols of oppression. But it also isn’t “false”.

It’s an opinion. You may have good reasons for having that opinion. But it’s still an opinion.

At this point, the conversation is over, because: We should never legislate opinions; our laws should always be based on facts and evidence. And that’s that; you can go ahead and skip down to the summary.

From here, I’m going to talk about a few of the sidetracks you’ll probably be dragged down when this argument comes up.

A symbol of freedom?!

I’m going to focus on specifically Muslim religious accessories for this section, and in particular the veil. This is just for the sake of making my job easier, and because the veil is the religious accessory most people are talking about when they’re talking about symbols of oppression.

From time to time, especially around World Hijab Day, you will hear the claim made that not only is the veil not a symbol of oppression, it is, in fact, a symbol of freedom. Or a symbol of empowerment.

On hearing this, a lot of people will completely flip their shit. They’ll pen outraged articles pointing out that a lot of women are still forced to wear the veil, and even those that aren’t have simply internalized the Bronze Age patriarchal values that created it.

Those things may be true, but they’re entirely beside the point. Whether veils are a symbol of oppression, freedom, empowerment, or whatever, is all just a matter of opinion. So no one’s “right” or “wrong”. There is no “true” or “false” here. There’s just different opinions. Some may be better justified than others. Some may be really, really dumb, or even horrible. But they’re still just opinions, not objective facts.

But for the sake of argument, I’m going to entertain this idea: What if the veil really is a symbol of freedom?

If you want to know why people wear the veil, you need to ask people who do wear the veil. Not people who oppose it. Not people who used to wear it, because they’d just be reporting things they don’t really believe or understand anymore – even if they could perfectly recall their thinking from their younger years, it will be filtered through a lens of their current thinking. You need to ask the people who are wearing the veil why they’re doing it.

Turns out that people veil for a number of complex reasons. But among those reasons are some pretty interesting perspectives.

-

Some women will point to the fact that European colonizers stripped their ancestors of their veils… while selling them as slaves. Wearing the veil now thus symbolizes their freedom from slavery.

Forcibly stripping them of their veil thus tells them that, in a way, they’re still slaves just like their ancestors. Their bodies still aren’t really under their control.

So, sure. In that light, it does make sense to see the veil as a symbol of freedom.

-

Others who wear the veil talk about a more complex idea of freedom.

Our society is still misogynistic and patriarchal. We’ve gotten better over time, sure, but there are still many ways that our society strips women of their agency and turns them and their bodies into public property. Even feminists who rage against the veil agree on this point. When a woman is out in public, she’s expected to be pleasing to look at, polite to anyone who approaches her – invited or not – and receptive to the desires of men. When a man catcalls or wolf-whistles at a woman on the street, she’s supposed to demurely accept their attention – if she doesn’t, she’s a “bitch”. The same idea applies for less obviously invasive or crude methods of trying to “pick up” a woman.

There are many men who see attractive women as a challenge to be mounted (perhaps literally), and will interject themselves into the woman’s space – usually without any invitation, or at best the most minimal “invitation” such as polite acknowledgement of their existence – to try a pick-up strategy. Most women will tell you that these attempts are usually uncomfortable, and sometimes even terrifying, because it can often be difficult to find a polite way to say “no” – they’re often forced to lie about being in a relationship, though that doesn’t always work – and there’s the very real risk of the man getting angry or even violent.

What women especially in European and North American societies have noticed is that once they put on the veil, men tend to leave them alone. Where women are generally viewed as mere sexual objects, the veil suddenly makes them “unavailable”. They no longer have to fend off unwanted advances, at least not as often. And they’re not treated merely as potential sexual conquests; they’re treated more like people.

I am not a woman, but from what I’ve heard from women, this isn’t an idea that’s crazy or difficult to grasp. I’ve heard several women say some days they wish they could go out in public and not be viewed as “women” – or rather, not be viewed the way society usually views women, which is as sexual objects. I’ve heard it expressed as the desire to be

seen as a man

(that was in the context of a woman engineer recounting how her technical suggestions were rebuffed with a compliment about her looks), and I’ve even heard a woman muse about going out with a mask or a bag over her head (her words). Those may have been passing fancies, but they express the same, underlying desire: to be able to exist in public without being viewed as a potential sexual conquest.It turns out that the veil actually does that.

Exactly why the veil does that is way beyond the scope of the discussion here. It may just be a case of the men’s lust being overridden by their hatred for Islam, but since most people are too civilized and polite to express naked hatred in casual interactions, from the woman’s perspective, she just sees the lust gone. Or it all may just be completely in the mind of the hijabi.

Whatever the case, this is a very common phenomenon reported by women who wear hijabs. For those women, the hijab represents freedom from the tyranny of socialized misogyny.

Once again, no one’s asking if you agree with these women’s opinions. The fact is, those opinions exist. They’re not entirely unjustified either.

-

There’s still yet another way that the veil can be viewed as a symbol of freedom. If you are unwilling or unable to take the opinions of women who wear the hijab seriously – and many people are like that – then one could make the argument quantitatively simply by pointing out the number of jurisdictions that legally require hijab versus the number of jurisdictions that legally ban it.

There are only three places in the world that I’m aware of that legally require the veil today: Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the Aceh province of Indonesia. That list is growing shorter, because the situation may be different in Saudi Arabia right now. There are several places, like Sudan or Malaysia, where vaguely worded laws or local requirements may suggest veils – for example, by requiring “modest clothing” without specifying what that means. And there are a few places where veiling is strongly “encouraged” by the authorities, sometimes with threats of violence, like in the Gaza Strip. (Veiling was mandatory in territories controlled by Daesh, but they were never a properly recognized state, and in any case, they’re about wiped out now.)

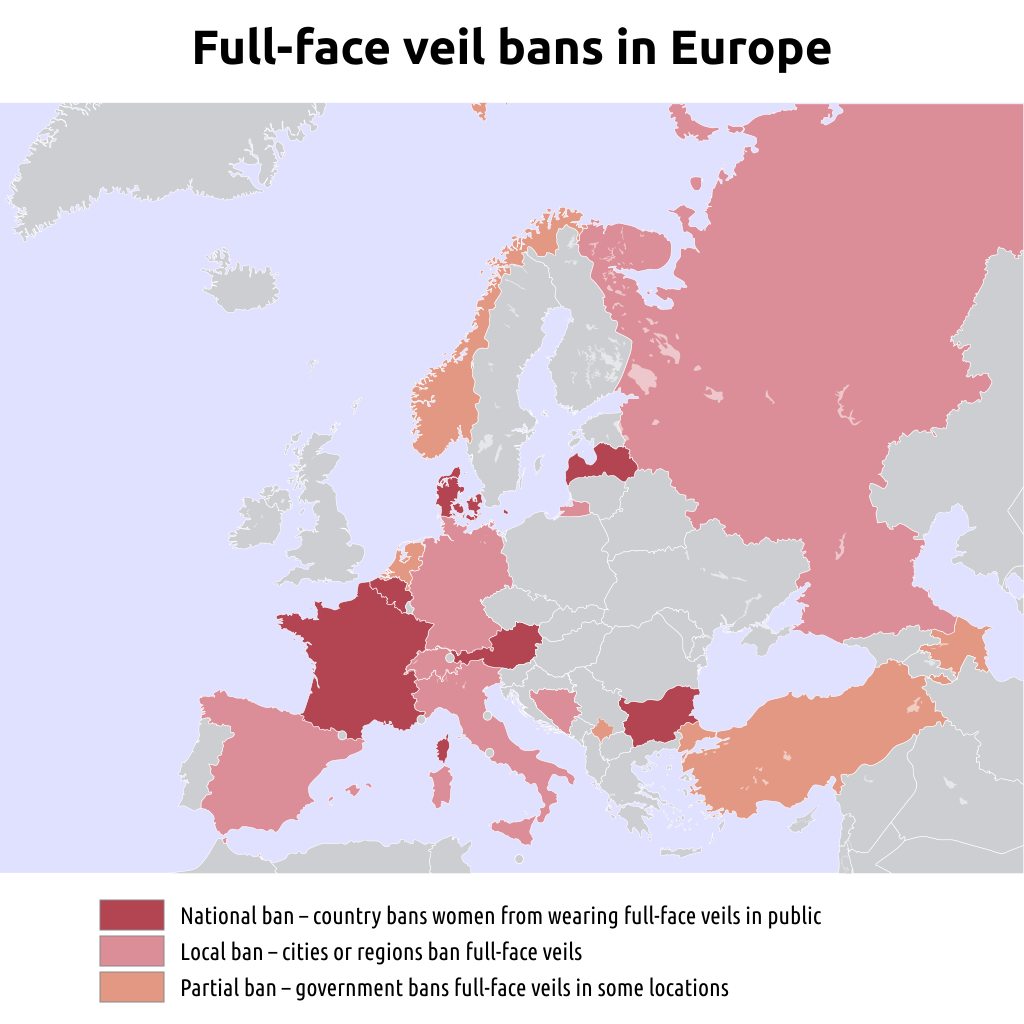

Meanwhile, the list of places that legally ban the veil is at least three times as long, and growing longer. It’s so long, people are making maps to keep track. Below is just the map for Europe. It doesn’t include Algeria, Cameroon, Chad, Gabon, Morocco, Syria, or Tajikstan, or places where there are local bans like in China and, yes, Canada (because there is already a ban in Québec, and an even more extensive ban under consideration). And of course, there are many places where there isn’t a legal ban, but still official pressure not to veil, like in Egypt, the Maldives, and Tunisia.

So just from a quantitative analysis, the veil is banned more places than it is enforced. Thus there is a much stronger argument that the veil is a symbol of freedom than that it is a symbol of oppression.

But again, that’s just opinion. It’s neither right nor wrong.

So there are ways to reasonably consider the Islamic veil to be a symbol of freedom, or empowerment.

That shouldn’t come as a surprise. Symbols do not have objective meanings; they can mean different things to different people.

(And just to shut down the inevitable retort: No I am not saying that symbols mean whatever you want them to mean. Symbols can have meanings in specific contexts that are either agreed-upon or assigned by an authority. But those meanings are not objective; they are, at best, intersubjective. A red octagon with the word “STOP” doesn’t mean traffic has to stop when I wear it on a T-shirt… but by decree of the road authority, it does mean that when it’s posted by the side of the road. It won’t mean anything to a person from an uncontacted tribe, though (and where I grew up, a stop sign looked like this; a red octagon meant nothing). A cross is not just a “generic grave marker”; it is, was, and always has been used to specifically mark Christian graves, and non-Christians do not use it (just do a Google Image Search for “traditional ____ grave marker”, substituting any religion). But there is no authority decreeing that religious accessories mean “oppression”, nor is there any social consensus.)

The Nazi play

When I point out that the meaning of symbols is a matter of opinion, not fact, and that the same symbol can mean different things to different people, inevitably along comes the Nazi play: “Well, then why can’t someone wear a Nazi swastika to work, but they can wear a Muslim veil?” (Once again, I’m forced to focus on the Muslim veil. Once again, that’s because it’s usually what people bring up.)

As an aside, it concerns me that it offends ban proponents so much that people can wear Muslim veils but not Nazi garb. Is it really necessary to even answer the question? Are you really concerned that Nazis can’t go goose-stepping around in public?

In any case, I’ll answer the question. In fact, I’ll answer it twice.

That’s because there are two answers, because there are two ways to ask the question. The first way is as a matter of practicality. If we can’t (because it would violate secularism, rights and freedoms, reason, practicality, etc.) ban people – even specifically just public servants – from wearing the burqa, for example, then why can we ban them from wearing the swastika? What’s the difference between the two?

I’ve already answered that question in a previous article in this series: “Proselytizing by accessories”. For a detailed response, read that article. For a brief summary:

It has nothing to do with whether the symbol is a religious symbol or not.

-

It has everything to do with the person’s reasons for wearing the symbol:

If you’re wearing the symbol for personal reasons – that is, for reasons primarily to do with your own identity and conscience – then it is okay. Religious accessories – at least, those at issue in religious accessories bans – are worn for private reasons, not public reasons.

If you’re wearing the symbol for public reasons – that is, for reasons primarily to do with communicating your identity or beliefs to others – then it is not okay. There is no part of any Nazi ideology that makes wearing the swastika an integral part of your being. Even goddamn Hitler didn’t wear it publicly all the time, for fuck’s sake.

The second way to ask the question is as a matter of theory. Forget about the rules for what is appropriate for workplace wear; let’s talk about what’s appropriate for display anywhere in the public view. So this goes way beyond people wearing religious accessories in government-controlled spaces. This extends even to standing on your own private lawn in a Muslim veil or waving a Nazi flag.

In this context, we can say the Nazi swastika is offensive to display anywhere in public. Why? Because there simply is no interpretation of the symbol in existence that isn’t horrific and evil. Yes, symbols can mean different things to different people, but when a symbol means a threat of violence to a large enough proportion of the population, it’s reasonable to acknowledge that as the meaning that matters most – any other meanings take a back seat to the threat. The Nazi swastika in particular represents a very real – and demonstrated – existential threat to huge sub-populations of Canadians: Jews, LGBTQ people, people of colour, and even secularists and atheists. And even those for whom it supposedly represents positive values, like nationalism, if pressed hard enough, will eventually be forced to admit beliefs that threaten minorities or opponents (how do you create a “white ethnostate” without forcibly ejecting “non-whites”?).

The Muslim veil, by contrast, does not represent a threat in general. Sure, one can find small groups that feel threatened by the veil, possibly because they hail from a place where it was actually used as an instrument of oppression. However:

-

The people who wear the veil are not doing so to show agreement with or support of the regimes or ideologies that carried out that oppression. Virtually everyone who wears the veil in North America and Europe (at least!) assert that it must be a choice, and in fact, would have less meaning if it were not a choice.

One could also point out the counter-fact that there are places – and many more places, as pointed out above – where the veil is banned. Thus, one is far more likely to find people who see the veil as a symbol of a lack of oppression than the opposite.

-

The average person will not assume that someone wearing a veil wants to advocate for oppressively enforcing it.

Quite to the contrary, the average Canadian usually assumes that a woman wearing a veil doesn’t really want to, and is only doing so under pressure. This is an ignorant and incorrect assumption, but it is what it is: it means that the veil is not seen as a symbol advocating the oppression of others.

So there is a clear, qualitative difference between the Nazi swastika and the Muslim veil. One almost always means the threat of violence – even by those who like it. The other almost never does – even to those who hate it. Thus, it makes perfect sense for the Nazi swastika to be considered generally offensive to display in public, but not the Muslim veil.

But of course, something shouldn’t be legally banned merely because it’s offensive. The Nazi swastika may be generally offensive to display publicly, but that doesn’t mean “there oughta ba a law”.

(And of course, there certainly shouldn’t be a law banning the Muslim veil. It’s worth noting at this point that many people who agitate for banning religious accessories – and specifically the Muslim veil – don’t also advocate for banning Nazi symbolism. Hmmm….)

There’s one more complication people like to try introducing: What about when the swastika is also a religious symbol?

That’s not a stupid question, because the swastika is a religious symbol in many Dharmic religions, like Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism. It’s also common in the symbology of many cultures, including some Indigenous Canadian cultures.

There is no religious tradition (that I’m aware of, at least) that requires wearing any symbols that include the swastika. That’s an important point, because it’s not enough for something to merely be “a religious symbol” for it to be a religious accessory that’s protected (that is, you can’t arbitrarily demand its removal without reason). It has to be a symbol that is being worn for deeply personal, conscientious reasons.

But okay, let’s say for the sake of argument that a religion exists that requires wearing a religious accessory that just happens to look exactly like a Nazi flag. I mean, already we’re in weird, non-existent, bullshit hypothetical territory, not reality. But what the hell, let’s play this game.

So the question is: Would someone be allowed to wear a religious accessory that’s identical to a Nazi flag?

The answer is: Yes.

In this hypothetical world where that strange religion exists with a coincidentally unfortunate symbol, members of that religion would be allowed to wear their required accessory. “But what about the Jewish people?” people who don’t actually care about Jewish people then ask. “Isn’t that offensive to them?”

The answer is that in that world, they – and everyone else – would have to be educated about the fact that the tilted swastika doesn’t always represent Nazism. They would have to learn to tolerate the symbol when it is being worn by members of the strange religion, though not necessarily otherwise.

There’s nothing weird or hypothetical about that either; it’s happened many times in this world. As people who hate religious symbols frequently point out, virtually all religious symbols can be associated with historical nastiness. People who come from cultures ravaged by the Crusades or otherwise victimized by Christianity – Canada’s indigenous peoples are a good example – have to come to terms with the fact that the symbol they suffered under means something very different to most Christians today. And those who suffered under Islamic persecution have to accept that most Muslims in Canada had nothing to do with that, and wouldn’t support it in any case.

(Last aside, I promise. Isn’t it interesting that veil ban advocates insist that people can never get over their experiences of Islamic persecution, yet completely disregard the experiences of people persecuted in the name of “European civilization”? Or science? Hmmm….)

To live in a multicultural society, we all need to be adults about these things. We need to recognize when symbols that we associate with oppression have very different meanings to others. To live together peacefully, we need to understand what they understand the symbol to mean, and – if it’s not threatening or oppressive – accept it and live with it. You never need to be a fan of it; you just need to accept that the people who use it are different, and let them be them. That’s what tolerance looks like.

Une petit ironie

So the Islamic veil is a symbol of oppression, eh? Because it has a religious history and was used to oppress a vulnerable population, right?

Take a look at the flag of Québec. For now, ignore the giant fucking cross in the middle of it. That would be too easy.

The Québec flag is made up of four sections separated by a cross in the middle, and at the centre of each section is a fleur-de-lis (⚜). The fleur-de-lis is not just a symbol of Québec, but of French Canada generally.

So… what does the fleur-de-lis mean?

Well, it turns out… it’s a religious symbol. It is associated with the Virgin Mary, though it’s also been associated – due to the three petals – with the Holy Trinity. It’s been used to symbolize notions of feminine purity and chastity – which are problematic ideas on their own – and it’s quite often been used to symbolize Roman Catholicism … which not only has a long and bloody history of oppression in ages past, it is currently in the middle of a scandal involving the sexual abuse of hundreds of thousands – at least! – of vulnerable children around the world. And that’s not even to mention the abuse of the nuns.

![[Fleur-de-lis]](https://www.canadianatheist.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/fleur-de-lis-200x273.png)

So … doesn’t that make the fleur-de-lis a symbol of oppression?

But wait! I’m not even done!

Because it turns out that when it comes to oppression, the fleur-de-lis has a much better claim on it than the Islamic veil ever has.

That’s because, back in the days of slavery, when a slave tried escape but was caught, they were branded with a fleur-de-lis as part of their punishment. That was apparently a common practice in several places around the world.

In fact, there was even serious discussion in Louisiana about treating the fleur-de-lis the same way they treat the Confederate flag. That is, recognizing it as a symbol of slavery and oppression, and removing it from all official iconography.

So if the Islamic veil is a symbol of oppression… why isn’t the fleur-de-lis as well?

And if it’s not just okay but necessary to ban the Islamic veil because some… not all… Québécois believe that it is a symbol of oppression, then wouldn’t it also be necessary to ban the fleur-de-lis?

Summary

“Religious accessories (or specific religious accessories) are symbols of oppression” is not a factual statement. It is an opinion statement. That means it can neither be objectively true nor false.

Because it is an opinion statement, it cannot be used to justify a law. Laws should be based on facts and evidence, not opinions.

That should be all that needs to be said about this “argument”.

But it apparently also needs to be said that the meaning of symbols can vary wildly from person to person. A veil may be a symbol of Islamist oppression to one person, and a symbol of freedom from European colonial oppression to another. There is no official body that defines the veil’s “true” meaning, or even any social consensus.

Even if there were a majority consensus that religious accessories – or a particular accessory, like the veil – symbolize oppression, that still wouldn’t justify banning them. As so many atheists are fond of saying: You don’t have a right to not be offended.

Unless a symbol’s primary meaning – as understood both by its opponents and its supporters – is threatening (or I suppose if the symbol itself is so violently ugly or gaudy that merely observing it causes physical damage to the sense organs), there is no rational or secular justification for banning it. A Nazi flag, for example, has never been used to symbolize anything but nationalism and racism, even by its fans (you can’t make a white ethnostate without somehow forcibly ejecting non-whites), and the ideologies it is universally used to symbolize represent a real, demonstrated existential threat to huge swaths of Canadians. And even then, the Nazi flag probably shouldn’t be banned by law! This is a job for social condemnation, not government jackboots.

You don’t have to like religious accessories or particular accessories (like the veil). But you do have to accept that some people are going to wear them. That’s what living in a free society looks like. There is no definition of “freedom” that looks like “people can do whatever they want so long as I approve of it”.

![[A photo of a woman in a hijab, with a red “no” slash overtop]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/religious-accessories-bans-300x300.jpg)

![[Flag of Québec]](https://www.canadianatheist.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Flag-of-Québec-200x133.png)

I spent several months bald and sun sensitive secondary to chemotherapy. I found a hijab style scarf wrapping more protective and comfortable than a hat. It seems obvious that the Quebec ban could not have forbidden me from this attire…..but they will attempt to ban other women from wearing identical attire because it is based on religion?

Yes, that’s another point that bears repeating!

Back when “burkini bans” were a thing in France, I wrote an article that included a picture of celebrity chef Nigella Lawson wearing a burkini to protect her sensitive skin at the beach, and asked whether she should be victimized by the burkini ban law. (Also, spoiler alert: a future instalment in this series uses the Queen wearing a headscarf as an example.)

I disagree that hijab is a sign of oppression no its not stop judging and people should be free of practicing their religion. Muslim women wear hijab for many reasons and not a single one of them is oppression. There’s much importance of Hijab in Islam its a sign of modesty and to be safe from lust.