Leo Igwe is the founder of the Nigerian Humanist Movement and former Western and Southern African representative of the International Humanist and Ethical Union. He is among the most prominent African non-religious people from the African continent. When he speaks, many people listen in a serious way. He holds a Ph.D. from the Bayreuth International School of African Studies at the University of Bayreuth in Germany, having earned a graduate degree in Philosophy from the University of Calabar in Nigeria. Here we talk about Nigerian and African humanism, the responsibilities of recognition, aims for the humanist movement, and a recent TED talk.

Scott Douglas Jacobsen: You are one of the most active Nigerian, and African for that matter, activists known to me. For many others, you have left a positive impression and impact, and show no signs of slowing down. What does this widespread recognition as an important voice mean to you?

Dr. Leo Igwe: The widespread recognition means more responsibility and more work. It obligates me to exert more efforts and sustain the momentum to further humanist ideals and values. It entails devising new and more potent strategies to make humanism flourish, and mainstream the rights and interests of nonreligious persons. The positive impression is a sign of a growing understanding or better, an enhanced realization of the importance of humanism; an indication that a long forgotten, long overlooked need for a positive non-religious outlook is now being fulfilled. In a country such as Nigeria, religion has an overwhelming influence. So it can be very difficult for humanist activists to make any significant impact because such an impression chips away on the rock of overbearing religions. Thus the recognition is a welcome development, a sign of hope that should propel me and other activists out there to do more and consolidate on the gains, the hard-won progress that the humanist movement has so far recorded.

Jacobsen: What does this also mean in terms of additional responsibilities from the recognition by peers and youth?

Igwe: It means striving to ensure that humanism takes its rightful place on the table of religions, philosophies or life stances, and that humanists and other non-religious people can live their lives and go about their everyday business with less and less fear. It means working to end persecution and discrimination against non-religious persons in the region. It motivates me to work for a secular Nigeria.

In Nigeria, those who identify as having no religion are in the minority; they are not reckoned with. Non-religious persons suffer systemic marginalization. For too long, persons without religion have been identified as a silent and sometimes, a non-existing minority. The maltreatment is unacceptable and I want to ensure that this situation changes and that the voice of humanism is heard when issues that affect the public are discussed.

In the coming years, I want to work to ensure that Nigerians grow up understanding that religion is an option, and knowing that they can leave religion; that they can criticize religion. I want to make sure that people in Nigeria are aware that humanism and atheism as options that they can explore and embrace.

Jacobsen: What are your current aims for the humanist movement of Nigeria, which you founded?

Igwe: I have two main objectives for the humanist movement. First is to strengthen the capacity of the movement to fulfill its role of providing a sense of community to non-religious persons. Active humanists are still few and far apart, but the challenge of organizing humanism, of growing and managing the humanist community is huge. The humanist movement needs to be positioned to meet these challenges. It needs mechanisms to robustly address the needs and interests of humanists. So I plan to identify such structures, locally and internationally, wherever they exist and put them at the disposal of the movement.

Second, I want to position the movement to meet the needs of the society. Some mistakenly think that humanism is exclusively for humanists. This is not the case. The humanist/freethought movement does not exist only for humanists but for the society as a whole. Religion and superstition negatively affect the religious and the superstitious. So the humanist movement should be enabled to support victims of religious extremism and irrational beliefs whether they are believers or nonbelievers. My goal is to capacitate the movement so that it can fulfill its obligation to humanists including defending the rights to freedom of religion or belief, freedom of expression and working to end harmful religious and superstitious practices.

Jacobsen: In a recent, and popular TED talk, you posited a positive life stance with humanism. One that even in spite of the difficulties in the past into the present for many Africans poses a positive future. How did you get the opportunity to present at TED?

Igwe: TED officials contacted me. They asked me to draft a talk on humanism and I did. The talk went through several revisions and very rigorous editing processes and rehearsals before it was finally accepted.

Jacobsen: How does humanism present a better future compared to other philosophies?

Igwe: Humanism presents a better future because it has humanity as its main reference. Humanism emphasizes human abilities and potentialities; that humans can overcome its problems and difficulties in this world. Unlike philosophies, especially those with supernatural resonation, humanism’s future is not an otherworldly infrastructure. It is this-world bound. Humanism stresses a future that is attainable and realizable in time and space. The future that it presents may be ideal but not completely a form of fantasy that only the disincarnated savour. It is not a strictly imagined idea that transcends reality, bereft of any trappings of the worldly. The future is not a post-mortem heritage that people can only enjoy and behold after they are dead. It is a future that is achievable in this life, in the here and now.

Jacobsen: In terms of the outcomes and responses to the TED talk, what has been the feedback?

Igwe: The responses have been encouraging. The talk has been viewed over seven hundred thousand times. I have received a couple of messages from those who listened and were inspired by the talk. I guess that the positive feedbacks, which the talk has so far elicited was mainly because such a perspective is a rarity in African discourses. I hope this is going to change and that there will be more TED and non-TED talks that make a strong case for humanism and freethought in Africa.

Jacobsen: Thank you for the opportunity and your time, Dr. Igwe.

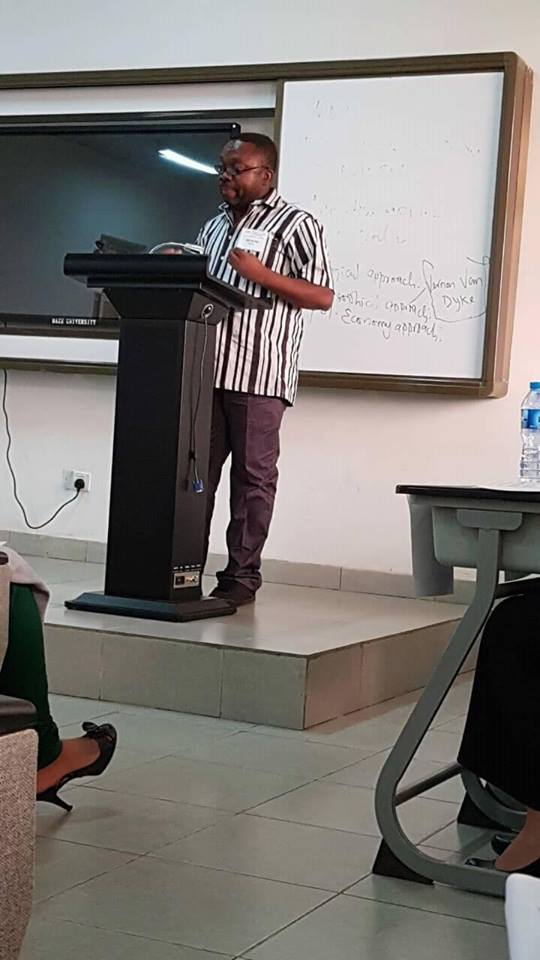

Image Credit: Dr. Leo Igwe.

Scott Douglas Jacobsen founded In-Sight Publishing and In-Sight: Independent Interview-Based Journal.